BEHIND BRIGHT COLOURS

Pierre Bonnard at The Tate Modern

|

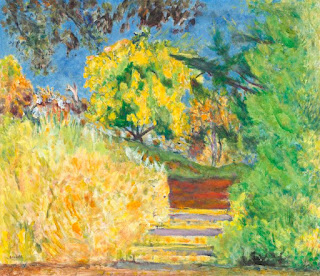

| Stairs to The Garden 1942 Pierre Bonnard |

I looked forward to seeing the Bonnard exhibition at the Tate Modern, however, whilst there is much to enjoy, I left with a strange feeling of claustrophobic melancholy. Something about the exhibition seemed sad and forlorn, more so owing, perhaps, to Bonnet’s reputation.

Pierre Bonnard, painter of domestic harmony, of glorious landscapes and gardens that assault the eye with bursting shells of colour, exploding yellows and reds, crimson and blue; the happy painter who through two world wars and the troubled inter-war years continued to paint pictures that depicted not only visions of intimate domesticity but the contentment of a settled life which had a love of beauty at its heart.

The Belle Époque is perhaps the most burnished period in modern history. This I suspect is a consequence as much of the cultural, scientific and artistic triumphs of the period as the manner of its ending. Few things provide a greater contrast than the real and imagined brilliance of Paris at the turn of the century and the mass slaughter of Verdun and the Somme.

If asked most people what immediately comes to mind about the Paris of 1900 I would hazard a guess that impressionism and Post-impressionism would feature high on most people’s list. And it was this movement that launched Bonnard’s artistic career. It was his glorious dawn, truly the days of wine and roses. The difficulty however of having a glorious time when you are young is it can so often lead, given that one cannot be 21 forever, to anti-climax, to disappointment and a dulling of the appetites. One must ‘grow up.’

Of course, there can be the satisfaction of marriage and domesticity, which can be considerable and not to be easily waved away as a form of bourgeois death of the spirit.[1]

What however if the brilliant dawn of your life concludes with the greatest moral, cultural and civilizational disaster of the modern era? To the slaughter of millions of young men, many of your friends and relations amongst them? Many things died in the trenches of Northern France foremost of al, perhaps, the beliefs that had fired the first wave of optimism that was the heart of the modernist project. It would never be bright confident morning again.

With the exception of one painting, said to depict Armistice day celebrations, the war barely features in the exhibition, yet is it too great a stretch to see this very act of repression as the source of the melancholy I, and indeed the friend I went with also, experienced?

|

| Self Portrait Pierre Bonnard |

There is another clue, and that is in Bonnard's self-portraits, which belie the cosy domesticity and vibrant beauty depicted in so much of his art. In these Bonnard appears a troubled man, someone not wholly at ease with himself.

There is a risk, of course, of striking a false note here, - Bonnardcertainly enjoyed the life of a famous artist who had established himself among the greats, like Cezanne, with whom he corresponded. He does not appear to have lacked material comforts. However, was there was another thread to his life, hidden behind the bright colours and glorious visions, one merely hinted at in the self-portraits? I think there was, and it is present in the exhibition if you look acutely enough.

The CC LAND EXHIBITION PIERRE BONNARD THE COLOUR OF MEMORY IS ON AT THE TATE MODERN BLACKFRIARS UNTIL THE 6TH MAY 2019

The CC LAND EXHIBITION PIERRE BONNARD THE COLOUR OF MEMORY IS ON AT THE TATE MODERN BLACKFRIARS UNTIL THE 6TH MAY 2019

[1] It is interesting how many of the Avant-Garde artists of the 20th century from Picasso to Max Ernst enjoyed lives of domestic tranquillity, albeit usually ‘out of wedlock’ as the phrase used to go. Bonnard himself defied convention in this way, but this was his only transgression in a life otherwise characterised by conventional domesticity. True he did enjoy one brief affair, but this was hardly unusual in contemporary France.